On March 26, 1351 – An extraordinary duel of knights occurred

Would you believe that in the middle of a brutal and drawn-out conflict in 14th-century France, an unusual and you could even say theatrical event occurred. It was a formal combat between two groups of knights, watched as if it was a football match by an eager audience, they even had refreshments, while the competitors, actually, took a halftime break. It was in some ways extraordinary, but it happened.

However, would you believe that this was not a tournament. It was war. But not war as we know it. This was The Combat of the Thirty when for a single day medieval warfare paused to indulge in an idealised version of chivalry.

A War Within a War

Before we get to the event itself, you need to know what was happening, what led up to it and to see it in its historical context.

The year was 1351, and in France it was mayhem. Since 1337 the Hundred Years’ War between England and France, had been raging. It was fundamentally a vicious conflict over succession and, as always, territorial control. Now if we go to Brittany, we see that here, the war had become particularly personal.

It all started after the death of Duke John III of Brittany in 1341. He died without a clear heir, naturally, a succession crisis exploded. As usual two rival factions staked their claims to the duchy:

- The House of Montfort, led by John of Montfort and later his wife, Joanna of Flanders, who were supported by the English.

- The House of Blois, led by Charles of Blois and his wife Joan of Penthièvre, supported by the French.

This struggle became known as the Breton War of Succession. It was violent and messy, there were constant skirmishes and sieges along with shifting loyalties. By 1351, both sides controlled different parts of Brittany, however, neither side could gain a decisive upper hand. Morale was low. Supplies were thin. The people were tired. And out of this bloodshed, a different kind of battle came about.

The Unusual Challenge

After 10 years it had got to a position that near the town of Josselin, two fortified castles stood a short distance apart, one with English-backed forces loyal to the House of Montfort, the other by French supported forces loyal to the House of Blois.

At this point frustrated, as they were getting nowhere by the lack of progress, Jean de Beaumanoir, commander of the Franco-Breton garrison, issued a bold challenge, which many think was because he was eager to revive the spirit of knighthood. He proposed to his opponent, Robert Bemborough, the English captain of Ploërmel, that they each select thirty of their finest warriors, knights and squires, and meet in open combat.

The idea wasn’t logical. As it wasn’t a duel, nor was it a battle in the traditional sense. Basically, it was a test of honour, a way to show valour and it was loony for him to suggest this in the middle the cruelty of war. To us today it may seem theatrical, even absurd, but to the medieval mind, chivalry and reputation were as important as tactics and territory.

Bemborough, famously known as a chivalrous man, accepted the challenge eagerly. They set the date as March 26, 1351, the site was chosen, it was to be in a field between the two castles.

The Stage is Set

This is the amazing bit, the local population loved the idea, and as word of the “event” spread, crowds gathered. Local nobles, townsfolk, and commoners all came to watch what as you could imagined was a medieval spectator sport. It became a special occasion as they brought packed lunches and drink. There were even stalls set up to supply the crowd with refreshments, just like a football match. It has been recorded that there were even makeshift stands set up so the spectators would have a better view.

The field was cleared. Then the rules were agreed upon.

- It was to be a fight to the death or surrender.

- There would be no outside interference.

- Only the sixty combatants would take part—thirty per side.

The sides then chose their fighters. They were chosen for their ability, expertise, courage, and status. They were the very image of knighthood, armour gleaming, standards raised, swords and lances at the ready. This was to be no petty skirmish—it was a carefully planned pageant of war, that was waged for honour, pride, and, naturally, in the names of the noble ladies they served. (More about these ladies later)

The Combat Begins

The battle commenced with enormous power, force, savagery, and anger. Swords clashed, lances splintered, and shields shattered as the two sides fought fiercely, each determined to uphold the reputation of their faction and honour their commanders.

Despite all the brutality, the combat was remarkably organised. As the fighting intensified, casualties began to mount. Blood flowed freely, but there remained a strange sense of discipline, no chaos, no retreat, just relentless hand-to-hand combat in the name of chivalry.

Then, on an agreed signal, both sides suddenly paused the fight, much like half time in a football match today. This allowed them to clear the field of the dead and wounded, tend to injuries, and, of course, share refreshments. It was weird, men who had been locked in mortal combat minutes before were now calmly drinking and resting, only to resume their fight when refreshed.

A Heroic Charge

After hours of battle, exhaustion was setting in. The English side, though brave and well-fought, began to falter. It was then that a dramatic moment turned the tide.

Guillaume de Montauban, a French squire, suddenly mounted his horse and charged directly into the English line, a highly unusual and surprising move, especially as most of the combat had been fought on foot. It surprised the English side as his charge broke their formation, and he reportedly killed seven of the enemy knights in quick succession.

With their ranks in disarray and morale shattered, the surviving English combatants surrendered.

Honour Even in Defeat

Although it had been a deadly encounter, the outcome was surprisingly civil. They were knights after all and they had rules to play by, with the result that the English prisoners were treated with respect, their wounds tended, and they were eventually released upon payment of a modest ransom, as was the custom among knights.

Jean de Beaumanoir, the French commander, despite being wounded and fainting from loss of blood during the combat, was hailed as a hero. His name would live on in song and story. The event was celebrated across France and beyond as an example of what chivalry could look like, even in the middle of a brutal and merciless war.

Chivalry or Propaganda?

In fact, to be honest “The Combat of the Thirty” was not a battle that changed the course of the Hundred Years’ War or even the Breton War of Succession. However, it did become a symbol, a shining example of medieval honour and knightly conduct.

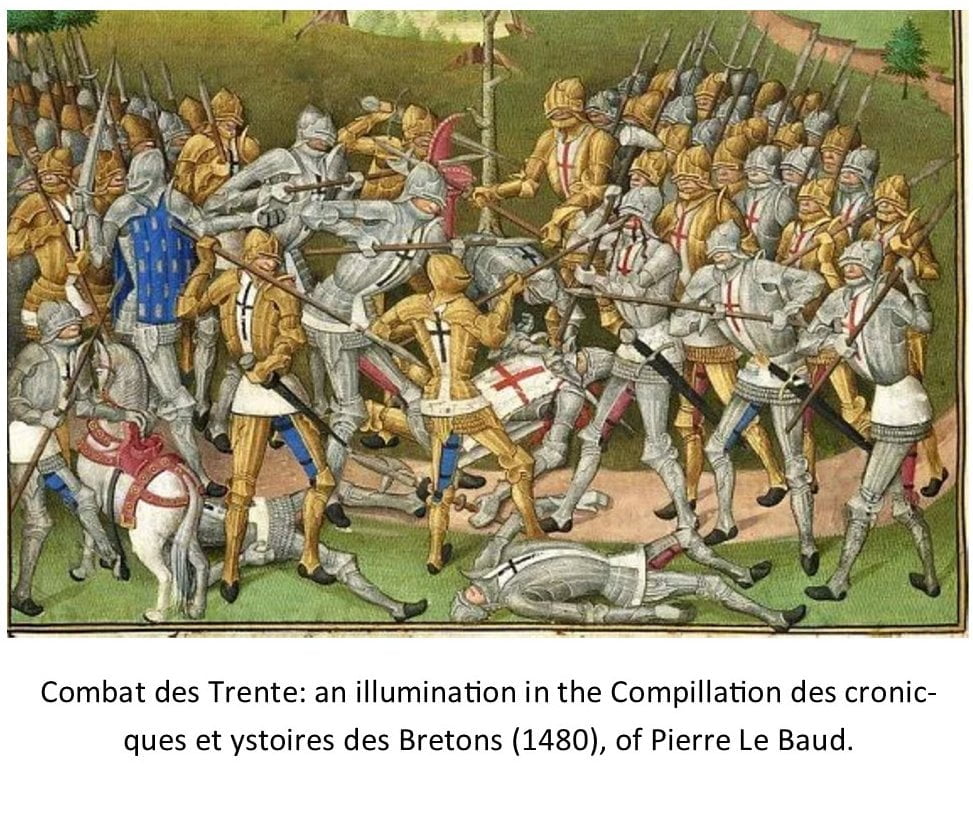

Contemporary writers described the battle in respectful tones. Ballads were then composed. Paintings were made. It became a story that was retold across generations, romanticised as a noble exception in an age of ruthless warfare.

However, some historians think that it may also have been a form of medieval propaganda, a way to boost morale, reinforce loyalty to noble houses, and distract from the gruesome realities of the larger conflict. After all, for the common people suffering under the burden of war, a spectacle of heroism might offer a brief escape and a sense of pride.

A Battle for the Honour of Ladies?

Now this is the fascinating bit of the story, it is the influence of two powerful women: Joan of Penthièvre, Duchess of Brittany (House of Blois), and Joanna of Flanders, wife of John of Montfort (House of Montfort).

Both were central figures in the Breton War of Succession. With Joan’s husband, Charles of Blois, captured and Joanna’s husband dead, the two women led their factions in their absence. They commanded the armies, rallied support, and were attempting to manage the political landscape.

Some writers suggest that the Combat of the Thirty was not merely about national pride or military frustration but was also fought for the honour of these two noble ladies, they were each a powerful symbol of their respective causes. If true, it reinforces the idea that the combat was not only a military affair but a deeply personal and symbolic gesture of loyalty or could it just have been that the commanders were trying to impress these ladies?

Legacy

The field near Josselin where the Combat of the Thirty took place is still marked today. A monument stands there, commemorating the fighters and preserving the memory of this unique episode in medieval history.

Conclusion

The Combat of the Thirty is only an odd footnote in the history of medieval warfare, but it gives us an insight into the beliefs of a medieval knight, his culture of honour, and the social codes that shapes the lives of those who, in those days, lived and died by the sword.

It is a story that tells us that war is not just fought by armies and weapons, but also with symbols, ideals, and imagination. On March 26, 1351, sixty men stepped onto a field not just to win or survive, but to prove something greater about courage, loyalty, and the human spirit.

Has this quality been lost in today’s relentless, high-profile, 24-hour media landscape? I would argue that it has. It has been overshadowed by the constant demand for immediacy, sensationalism, and superficial engagement.

Isn’t history fun?

10 Discussion questions:

- What does the Combat of the Thirty reveal about the values and ideals of medieval knighthood and chivalry?

- How was this event different from both a traditional battle and a tournament, and why might those differences be important?

- Why do you think both sides agreed to pause the fight for a break, and what does that suggest about warfare at the time?

- In what ways was the Combat of the Thirty used as a form of propaganda during the Hundred Years’ War?

- How might this event have affected the morale of soldiers and civilians involved in the wider conflict?

- What role did Joan of Penthièvre and Joanna of Flanders play in the background of this event, and how might their influence have shaped it?

- Why do you think spectators treated this deadly combat like a sporting event? What does that say about medieval society and entertainment?

- Do you think the ideals shown in the Combat of the Thirty were genuine or staged? Why?

- How does this story challenge our modern understanding of what war looks like?

- Should events like the Combat of the Thirty be remembered as heroic moments of honour, or as distractions from the cruelty of war? Why?

To help you to learn about this amazing event click on: