England was Confused

It is 1688, and England was in turmoil.

King James II, who was a Catholic, was becoming increasingly unpopular with both his Protestant Parliament and his people. He believed in the divine right of kings, which meant that monarchs were only answerable to God. This was the problem, as the Parliamentarians were Protestants and didn’t believe in the Divine right of Kings, that’s what they fought and won the civil war on 40 years before. This caused the friction as they didn’t want to go through all that again. It wasn’t the only area of dispute; it was also the King’s willingness to place Catholics in positions of power. This was becoming too bitter a pill for Parliament to swallow.

As Parliament’s fears grew with the Kings increasingly dictatorial tendencies, he was becoming at odds with England’s fiercely Protestant Parliament. As they watched the king sidestep established norms and introduce more Catholics to key positions, the situation reached a boiling point. For the sake of the country Parliament knew that it had to find a solution.

That solution

The solution, if they could make it work was across the North Sea in Holland. It could be with Prince William of Orange, Stadholder of the Dutch Republic, a determined opponents of Catholic France, who happened to be married to Mary, the Protestant daughter of King James II.

William had from an early age learnt the skills of politics; he had been seasoned by years of warfare, which meant that he knew that the correct alliances were critical to maintaining power. For William, an alliance with England meant a secure ally in his battles with France.

To explain he had been elected Stadholder, the elected head of state, at just 18, in 1672, which the Dutch call The Year of Disasters, when his homeland was nearly overrun by the French forces of Louis XIV. William had fought tooth and nail and secured the survival of his country. The result was he had a deep hatred of France, and didn’t trust them as they were using their power as a Catholic nation to threaten Protestant interests across Europe. William saw an alliance with England as essential to achieving his broader ambitions.

So the stage was set, what happened next?

A Calculated Gamble

The spark to start was a daring invitation. In a move that could have easily led to disaster, seven influential English Parliamentarians secretly invited William and Mary to come to England and “save” the nation. Their invitation used the fact that Mary was James II’s daughter, which was a legitimate link to the English throne. However, this connection didn’t mean that his reception in England was by any means certain. For this reason, William realised that he had to bring along an army, which he hoped wouldn’t need to fight.

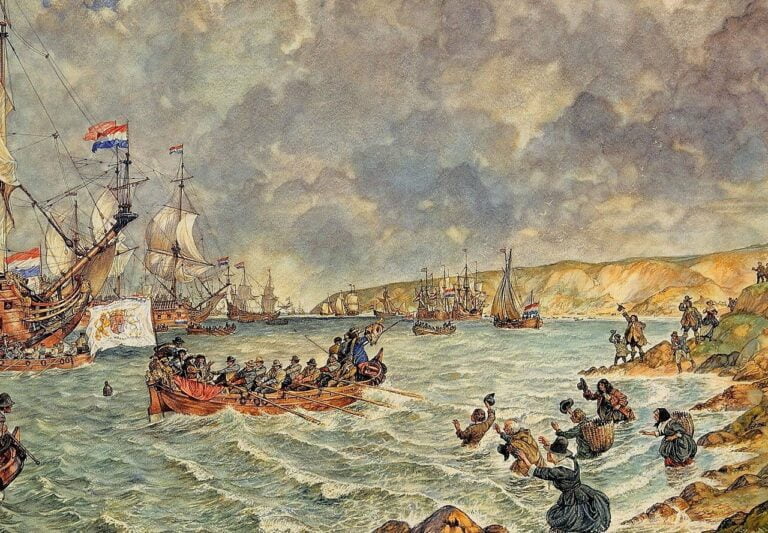

He wasn’t going to take any risks and he prepared for one of the largest military mobilizations of the 17th century, he assembled an enormous fleet of 463 ships. He then sailed down the English Channel from Dover all the way to Torbay, it wasn’t to launch an assault but to demonstrate power and preparedness. You see it could be seen from the coast floating down the channel, which was, of course, what he wanted. While at the same time showing his intentions to King James.

Finally, on November 5, 1688, William landed at Torbay with this formidable army of over 14,000 men, but he hoped the sight and size of his forces would prevent bloodshed. His gamble paid off. As he reached town after town, the English people welcomed William and his men. Despite James II’s initial efforts to mobilize an army of 30,000 men, William encountered little resistance. In fact, in one of the most surprising twists, over 26,000 of James’s troops sent to stop him deserted, they appeared not to want to fight for a king who had lost the trust of his people.

The March to London: A Bloodless Coup

As William’s forces moved towards London, King James realised that his hold on power was crumbling. He understood that it was all over, he accepted the inevitable. He fled to France, effectively abandoning the throne and leaving England in a precarious state.

This was William’s stroke of genius

When William reached London, he chose not to claim the throne outright. He did something different; he took a carefully calculated step, he called a Convention of Lords and MPs.

Such a convection is technically not a Parliament, as Parliament has to be summoned by the king. The clever bit is that by gathering a convention instead of seizing power directly, William ensured that his ascent to the throne would be seen as legitimate and in line with England’s political traditions. The Convention granted William and Mary the throne, which was supported by the political elite, it had the effect of changing what could have been seen as a foreign invasion into a “lawful” transfer of power. By using his political skills William was able to position himself as the rightful sovereign chosen by the English establishment.

Revolution or Invasion?

This brings up the question was The Glorious Revolution truly a revolution, or was it an invasion in all but name?

It appears that to avoid admitting that a foreign power had successfully “invaded” England, it became known as the “Glorious Revolution.” In a way it was glorious, gloriously bloodless, gloriously swift, and gloriously beneficial to both parties.

England avoided a second civil war, and William secured an alliance that would strengthen his position against France.

However, the reality is that the Dutch had indeed invaded England. Although the revolution was peaceful, the events of 1688 still mark the only successful foreign invasion of England since the Norman Conquest. The irony is not lost on those who view it as an invasion: a massive Dutch armada sailed into English waters, landed troops, and replaced the sitting monarch, and they did all this without firing a shot. However, for the English, it is more palatable to remember the Glorious Revolution as a victory for Parliament rather than an invasion by the Dutch.

The Legacy of the Glorious Revolution

It made long term changes to our English political landscape that are still in place today. The risk taken by Parliament in 1688 set a new model for the monarchy’s relationship with Parliament. Over the years that followed, Parliament gained substantial power, particularly in matters of succession and religion. The Bill of Rights of 1689, a year later, further limited the powers of the monarchy and laid the foundation for the constitutional monarchy we have today.

Conclusion

So, to answer the question, Did the Dutch invade England?

If you think about it you could say they did, but how can it be an invasion when they were invited?

While there was no violence, which we usually associate with revolutions, it very dramatically altered the English political landscape, leading to a shift in power that paved the way for today’s modern democracy in Britain.

Isn’t History fun?

Here are ten thought-provoking questions based on the blog:

- What were the main factors that led to King James II’s unpopularity with his Parliament and the English people?

- How did the religious tensions between Protestant Parliament and Catholic monarchy influence England’s political landscape in 1688?

- Why did English Parliamentarians view an alliance with William of Orange as the solution to their concerns about King James II?

- What was the significance of the “invitation” sent to William and Mary by the seven English Parliamentarians, and why was it a risky move?

- How did William of Orange’s military mobilization and display of force contribute to his success without engaging in battle?

- Why did so many of King James II’s troops desert, and how did this impact William’s march to London?

- What was the purpose of William’s decision to summon a Convention of Lords and MPs instead of claiming the throne directly?

- In what ways did William’s careful actions help transform what could have been seen as a foreign invasion into a “lawful” transfer of power?

- Why is the Glorious Revolution sometimes considered an invasion, despite being a largely bloodless event?

- How did the Glorious Revolution and the subsequent Bill of Rights of 1689 reshape the balance of power between the monarchy and Parliament?

These questions encourage readers to delve into the historical, political, and philosophical aspects of the Glorious Revolution.

For more information o this please click on:

© Tony Dalton