Tulip Mania discussed

In the 17th century Holland had the highest per capita income in the world. This was because the Dutch Republic’s economic and financial system was at the time the most advanced and sophisticated ever seen in history. It is called the Dutch Golden Age. However, their sophistication in financial matters had its downside, it led to Tulip Mania.

Tulip Mania is generally considered to have been the first recorded speculative bubble or asset bubble in history.

Amazingly, it didn’t damage the prosperity of the Dutch Republic, which had the highest per capita income in the world between 1600 and 1720. The term “tulip mania” is often used to describe a large economic bubble, when the price of something moves spectacularly upwards, then dramatically falls.

What happened was due to Holland’s success, while at the same time the fashionable ladies of Paris had acquired a taste for special tulips. These ladies wanted to wear tulips with mosaic patterns, they had to be grown from specific bulbs that had a rare virus.

Yes, you guessed it, the only place where you could get this rare bulb was in Holland.

The Dutch had this successful economy, which along with a demand for these special tulips, resulted in the market for tulips going stupid.

The Financial Instrument

Now, this is where the Dutch financial acumen came in. The sophisticated Dutch financiers came up with what today we would describe as a financial instrument. It was a complex financial tool, which in the end led to the disaster that followed. You see it meant that you didn’t have to pay the full price for the tulips, well, not to start with!

Now, this is where the Dutch financial acumen came in. The sophisticated Dutch financiers came up with what today we would describe as a financial instrument. It was a complex financial tool, which in the end led to the disaster that followed. You see it meant that you didn’t have to pay the full price for the tulips, well, not to start with!

So, what was this scheme that appeared so brilliant? It was simple:

- you agree the price with the buyer

- In return the buyer agreed to accept an initial deposit of 2.5% of the agreed price

- you then agree to pay the rest when the tulip is sold.

It was simple, as the price of tulips was rising daily, you just had to wait until the price went up and then sell it. Simple!

It was a guaranteed way to make money, especially if you didn’t have much money, as the prices of tulips were only going up!

Scottish author Charles MacKay in 1841 explained it this way:

“A golden bait hung temptingly out before the people, and one after the other, they rushed to the tulip-marts, like flies around a honey-pot, Nobles, citizens, farmers, mechanics, sea-men, footmen, maid-servants, even chimney-sweeps and old clothes-women, dabbled in tulips.”

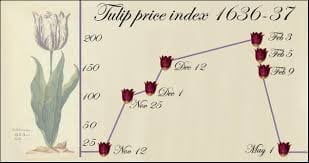

However, look what happened to the price of tulips:

- In 1634 Tulips sold for a few florins

- January 1637 Tulips price reached 6,390 florins

- February 1637 Tulips back down to a few florins!

What happened in 1637?

In 1637 a tulip sold for 6,390 florins!

In 1637 a tulip sold for 6,390 florins!

To explain how ridiculous this price was. In those days a large mansion on the Buitenhof, which is in the centre of the Dutch capital, The Hague, sold for just over 3,000 florins!

Therefore, at this price those people sitting on their forward contracts decided to sell.

Ouch!

Everyone put their tulips up for sale at the same time!

The result, of course, was that there were no buyers as everyone realised that no tulip could ever be worth this money. The price came crashing down, leaving an awful lot of people owing a different group of people a frightening amount of money.

This was a crisis!

What were the consequences?

T he first thing to recognise was that most of the bulbs were not even there, they were, in fact, still in the ground!

he first thing to recognise was that most of the bulbs were not even there, they were, in fact, still in the ground!

This meant that most of the money hadn’t been paid, in fact, it wasn’t due until the bulbs were handed over in May or June. Therefore, those who lost money in the February crash did so only theoretically, they might not get paid later. Anyone who had both bought and sold a tulip on paper since the summer of 1636 had obviously lost nothing. Only those waiting for payment were in trouble, and some were able to bear the loss.

Did it damage the growth of the Dutch Economy?

No!

One reason was that the total value of the trade in bulbs was only a small part of the Dutch economy.

Even more surprisingly, it turned out that tulip dealing was only a small part of the bulb business, which meant there were few bankruptcies. It was the speculators profits that disappeared, the most they lost was personal.

Nevertheless, people did suffer from the crisis. The growers were left with huge quantities of worthless tulip bulbs, while speculators who sold or mortgaged their estates lost almost everything. However, the tulip crisis did not in the end affect the whole economy, somehow, the government was able to keep it brief and localized.

It appears that most of the money used in the tulip boom came from organisations involved in bulb trading and not from financial institutions. This meant that the losses were kept to the bulb market and not generally to the banks, leaving the Dutch economic system unaffected. Therefore, the Tulip mania did not lead to a huge credit crisis, as usually happens when a market booms then crashes.

The real reason was, as I said earlier, that Holland was Europe’s economic powerhouse, it could take the hit. The Dutch were able to keep it like this all the way into the next century.

There were many lessons to be learnt from tulip mania. The most important one is the risk of buying on credit in a boom. The risk is that as you don’t have the money, should the prices fall, as eventually they usually do, where does it leave you?

Isn’t History Fascinating?

10 questions to discuss:

What factors contributed to the prosperity of the Dutch Republic during the 17th century, leading to what is known as the Dutch Golden Age?

Describe the phenomenon of Tulip Mania. What was unique about it in terms of economic history?

How did the demand for special tulips contribute to the Tulip Mania?

Explain the financial instrument devised by Dutch financiers during Tulip Mania. How did it contribute to the speculative bubble?

According to Charles MacKay, how did people from various walks of life participate in Tulip Mania?

Detail the significant price fluctuations of tulips during Tulip Mania, specifically highlighting the extreme price reached in 1637.

What were the consequences of the collapse of tulip prices in February 1637?

How did the Tulip Mania crisis impact different stakeholders, including growers, speculators, and financial institutions?

Discuss why the Tulip Mania did not significantly damage the overall Dutch economy despite its severity.

What key lesson about credit and speculative bubbles can be learned from the Tulip Mania episode?

To learn more click on:

© Tony Dalton